Where should we plant mangroves?

A data-driven look at East Java’s coastline

For years, discussions about mangrove restoration along the Indonesian coastline have been guided more by intuition than investigation. We hear familiar claims repeated almost with ritual certainty: mangroves protect our villages, guard our shores, and must be planted everywhere before coastal damage becomes irreversible. These sentiments are heartfelt, but they skip over the crucial bottleneck in coastal conservation: restoration resources are not infinite. Land, funds, and time run out long before good intentions do. If that is the case, then a harder question is where should mangroves actually be planted first?

This single question changes everything. It forces us to admit that not every coastline is equally threatened, not every community is equally vulnerable, and not every mangrove planting delivers meaningful protection. Treating restoration as a uniform activity across space ignores the geography of risk, the biology of mangrove growth, and most importantly, the people who depend on the coast.

Before deciding where to plant mangroves, we need to understand who lives along these coastlines. Java is one of the most densely populated islands on Earth; coastal land is not just scenery but space where millions of people build homes, livelihoods, and aspirations. Planting mangroves on an empty shoreline may be ecologically admirable, but it does nothing to reduce human vulnerability. In contrast, planting them near densely inhabited estuaries can alter the future of entire communities. This is why population density is not decorative in restoration planning. It is diagnostics that reveals where ecosystem failure becomes social catastrophe.

Understanding where people live is only the first layer. The second layer is ecological: where are mangroves currently located, and where are they absent? Existing mangroves act like living infrastructure, they dissipate wave energy, trap sediment, slow tidal intrusion, and reduce erosion. Their absence means a coastline stands exposed. Their presence means restoration efforts must shift from planting to protecting what already stands.

Once people and mangroves is understood, we can finally address restoration with a framework grounded in evidence. To do this, I used the Coastal Vulnerability model from the InVEST suite, developed by the Natural Capital Project. Unlike broad national assessments, this model does something remarkably practical: it divides the coastline into small segments and calculates how exposed each one is to physical hazards. It evaluates wind, waves, storm surge potential, sea-level rise, and elevation, and then performs a counterfactual analysis, what would exposure look like if mangroves were not present?

The raw exposure maps are informative, but exposure by itself doesn’t answer the restoration question. A hazardous coastline with no residents might be a conservation target, but it is not a restoration priority. A moderately exposed coastline sheltering thousands of people could be one storm away from disaster. Restoration becomes meaningful only when physical exposure intersects with human presence and ecological feasibility.

So I constructed a restoration index built on three interlocking ideas:

- Where mangroves are absent, vulnerability is unbuffered

- Where exposure is high, failure is costly

- Where population density is high, failure becomes human tragedy

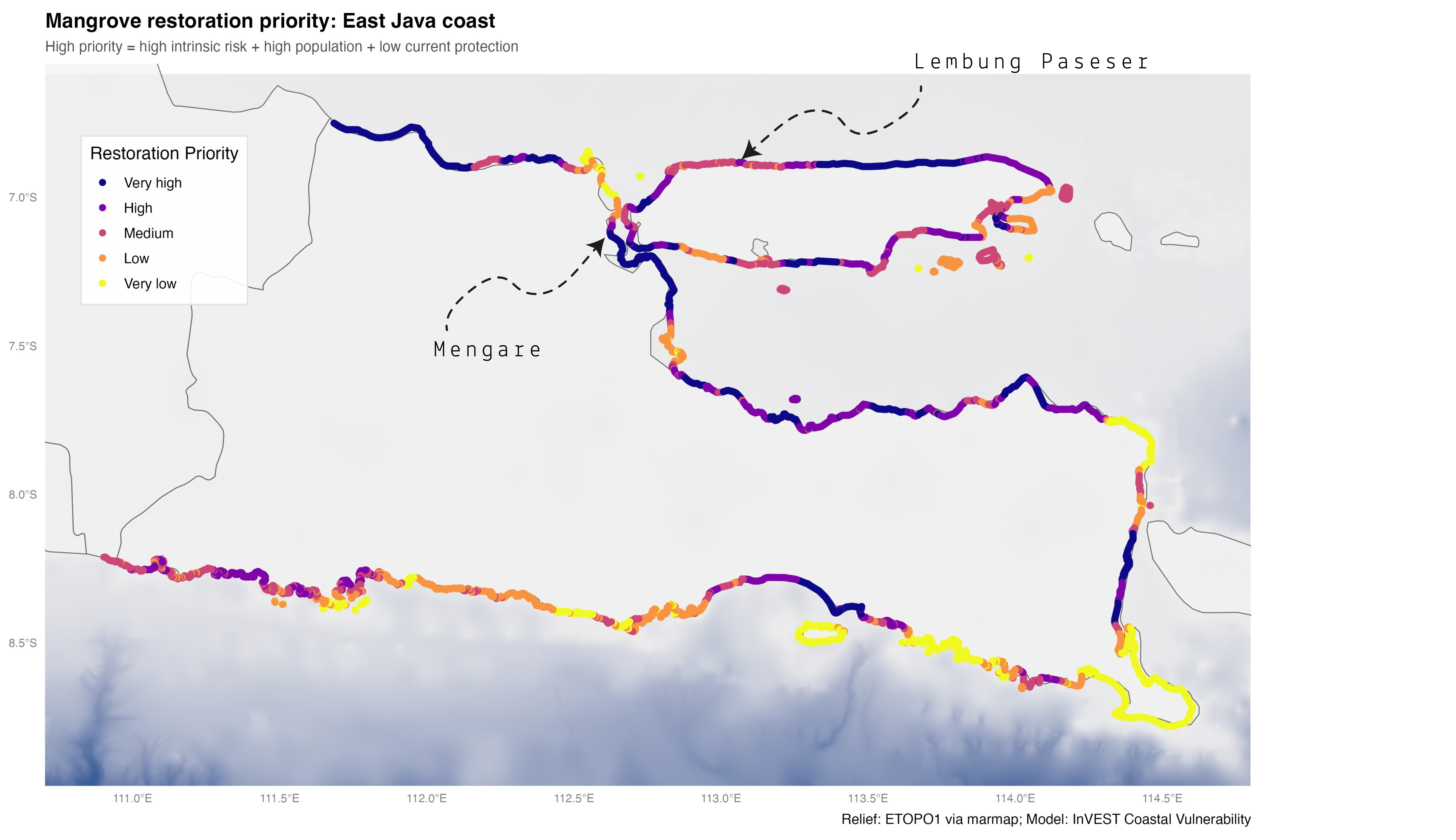

When these factors are combined, the results reveal a very different map of priority than intuition alone would suggest. The highest priority zones for mangrove restoration in East Java are not the dramatic, wave-battered southern cliffs frequently shown in environmental posters. They are the quiet, low-lying deltas of the north, places shaped by centuries of sedimentation, where storm surge creeps inland, and where thousands of people live within walking distance of the tide line. In these places, mangroves are not scenery. They are safety.

Seeing the three maps together that includes population density, mangrove presence, and restoration priority creates a narrative that intuition alone could never reveal. Mangroves do not need to be planted everywhere. They need to be planted where people are unprotected, where physical danger is real, and where ecological conditions allow mangroves to thrive. Restoration that ignores these factors risks being symbolic. Restoration that incorporates them becomes strategic.